Jon Pretty

Introducing Skala: A New Vision for Dotty

We are very proud today to be able to reveal that Dotty, sometimes referred to as “Scala 3”, will now officially be known as, “Skala”. And for the first time, we are delighted to announce that Skala will be adopting German keywords and syntax.

Designing programming languages based on English is a recurrent historical leitmotif, but – this April – we felt that as Britain moves away from the European Union, taking much of the influence of the English language with it, now is the perfect time to make the transition to a superior language.

Just a few years ago Dotty was a mere twinkling in the eye of Martin Odersky, but it was then that he first envisaged a successor to Scala based on German. We met up with Prof Odersky, Skala’s übermensch, at the Skala launchfest in a Munich biergarten to find out more about this exciting development.

“I always felt that the English in Scala was a weak ersatz, and risked leaving it in a hinterland in the long-term, so I realised then that I had to take this decisive diktat to set Skala on the right track for a bright future. It’s a very pragmatic move; very realpolitik…” says Odersky.

The Scala community aren’t neanderthals, though the transition may be harder for some people than others, so as long as we are all finding our feet in “Skala kindergarten”, we will not be making the English keywords verboten immediately. And any existing Scala users concerned about feeling like ausländers should not worry: over the coming months, the Skalazentrum (formerly the Scala Center) will have a blitz to convert existing Scala source code to Skala.

The Skalazentrum continues to do some very important work on Skalafix, supporting automatic code rewriting between Scala and Skala. It already supports many of the Glitzy new features first introduced in Dotty, and support for German keywords will be a trivial addition.

About the Changes

Martin goes on, “One aspect of Scala’s keywords I always liked was that val,

var and def were all the same length, so identifier names would align

vertically. It just looked beautiful! We’ve managed to retain that property

with the new keywords, unveränderliche, opportunistisch and

verfahrensweise, whilst giving each of them more character, and indeed more

characters. I’m particularly fond of opportunistisch, which exemplifies how

every programmer should feel about using mutable state. And while val and

var were near-doppelgangers, unveränderliche and opportunistisch are now

much more easily disambiguated.”

Some users may have angst about typing characters such as ü and ß, but

Odersky dismisses this idea: “Being completely unable to enter half the syntax

on an English keyboard may make coding slower, but that never seemed to hold

Scalaz back.”

It won’t be long before talk of do/while loops, try/catch/finally

blocks and if/then/else expressions, are a thing of the past, and

mach/während loops, versuche/fang/endlich blocks and

sofern/gegebenenfalls/andernfalls expressions become part of the

programming zeitgeist.

We took choosing the new German keywords as an opportunity to improve upon

their old English variants. For example, ich sounds much more personal than

this, implementationsdefiniert conveys the meaning of abstract so much

more concretely, and erbt saves typing a few characters over the more verbose

extends. Skala also introduces the new keyword, auffaltungsanleitung –

called inline in Dotty – but now with a more explanatory name.

“Also, many people criticize the concept of implicits as masochistic. That’s

why I decided to not talk about them, to keep quiet, to be stillschweigend in

a sense. And I’m very happy that the new keyword makes this feeling implicit.”

“I have often been approached about the suitability of Scala in the enterprise.

Maybe it’s just schadenfreude, but to better reflect corporate hierarchies,

super’s replacement keyword, vorgesetzte, makes it clear that the

programmer has to defer to their manager.”

In this update, we also wanted to acknowledge that German is not the only

language programmers use, so we settled on replacing the return keyword,

which we didn’t care much about anyway, with retoure, a French word loaned to

German.

Here is a full list of Skala keywords:

implementationsdefiniert |

muster |

klasse |

fang |

verfahrensweise |

mach |

andernfalls |

erbt |

unrichtig |

letzte |

endlich |

für |

gegeben |

sofern |

stillschweigend |

einführen |

auffaltungsanleitung |

faul |

kompilationsroutine |

vergleiche |

erzeuge |

nichtig |

entität |

überschreiben |

paket |

vertraulich |

zugangsbeschränkt |

retoure |

versiegelt |

vorgesetzte |

gegebenenfalls |

ich |

wirf |

charakterzug |

wahrhaftig |

versuche |

sorte |

unveränderliche |

opportunistisch |

außerdem |

währen |

vorfahrtGewähren |

Try it out!

One of the biggest ongoing efforts of the newly-renamed Skalazentrum is the development of the new collections library, which will form the basis for the data structures we use on a daily basis in Skala. We have already completed work on translating the current Strawman Collections to Skala, and to offer a first glimpse of the improved readability of Skala code, you can browse some Skala source code here (dead link: https://github.com/propensive/collection-strawman/blob/master/src/main/scala/strawman/collection/View.scala). We are working with GitHub to support syntax highlighting for Skala, but it’s not there yet.

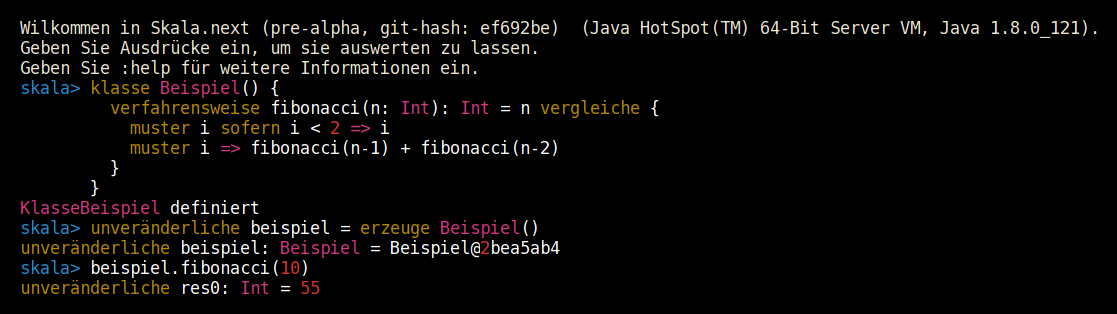

You can also try out Skala for yourself today (https://github.com/fmasion/skala) with the fully-functional compiler and REPL. Instructions on running the compiler are in the README file (https://github.com/fmasion/skala/blob/master/README.md).

Future Work

This is just the first step in Skala’s journey, but that journey is not yet complete.

One of Scala’s great innovations was support for using method names in infix position, and Odersky would like to take that one step further to make all method applications postfix by default. As Mark Twain observes in his appraisal of German sentence structure, “…the writer [appends] ‘haben sind gewesen gehabt haben geworden sein,’ or words to that effect, and the monument is finished.” To Odersky, postfix verbs are like “the alpenglow of a sentence”.

A problem Scala always suffered from was that it was never clear what was an object, or “noun”, and what was a method, or “verb”. Soon, Skala will require that all objects start with a capital letter, and all methods start with a lower-case character. This will mean some changes to pattern matching, but as Odersky says, “most people never knew the rules about capitalization of identifiers in patterns anyway, and the backtick syntax will continue to be available, so for me it’s worth the compromise”.

Another great feature of German, separable verbs, is on the cards for Skala,

too. Odersky explains, “People often accuse German of combining multiple words

into a single word. But English can be just as clumsy: Why use just one word,

“map”, to describe the method of a functor when, conceptually, you bilde the list

ab? That ab isn’t just some insignificant particle; it changes the whole

meaning of bilde!” So Skala will soon be supporting this convenient syntax

for separable method names,

list.bilde(_ + 1)ab

and remembering that verfahrensweise is the keyword formerly known as def, we

can define this new method with,

verfahrensweise bilde[A](f: E => R)ab = ...

One more planned change to Skala’s syntax is the elimination of unnecessary

spaces between modifiers and definitions. It was always a frustration to

Odersky that abstract override lazy val could not be a single word. “It’s a

single concept, so why not?” he asks, incredulously. Yet the reason was always

that forming compound words simply didn’t work so well in English; but in

German, writing implementationsdefiniertüberschreibenfaulunveränderliche is

completely natural, so we intend to fully embrace it.

Get involved!

We have come a long way in getting Skala to this stage, and there continues to be much exciting work going into the language. With the help of organizations like the Skalazentrum, Typstufe, events like Skala World and inclusive groups like SkalaBridge, we hope to grow the community around this ambitious new language. So I hope you will join with us in embracing this bold step towards a better zukunft.

Editor’s note: this article is dedicated to all the non-native English speakers who use, persevere with and contribute to Scala in English. Thank you. We are also grateful to Lars Hupel for his assistance with some of the translations.