Adrien Piquerez, Scala Center

sbt is a prominent tool of the Scala ecosystem. Yet it is poorly integrated in our IDEs and code editors, which are used to relying on internals or third parties to perform operations like compiling, running and testing.

From this lack of integration derives a number of inconveniences:

- Duplicated compilation times between sbt and the IDE

- False compiler errors on the IDE

- Outdated dependencies causing run-time failures

- Conflicting Java versions

We, at the Scala Center, are dedicated to improving the tooling that benefits all Scala users. We collaborated with JetBrains on designing the Build Server Protocol (BSP), a communication protocol between IDEs and build tools. It has since been adopted by some major players of the Scala tooling ecosystem, among which IntelliJ Idea, Metals and Bloop. Yet it was not supported by sbt until recently.

Today we are proud to announce that support of BSP has been shipped into sbt 1.4.0.

As we will see in more details, BSP in sbt improves the integration of sbt inside IDEs and code editors. It provides the user with a unified working environment that is:

- Optimal in terms of compilation speed and reliability

- Centralized around the sbt build definition

- Highly customizable, by benefiting from the sbt task graph

You can already try using sbt as the build server in IntelliJ Idea or Metals by following the instructions in this Scala contributors post or in the sbt 1.4.0 release note. (Metals integration will soon become much smoother thanks to this PR by Chris Kipp)

Background

Support of BSP in sbt is a Scala Center Advisory Board Proposal, dated January 2020, initiated by Justin Kaeser from JetBrains and submitted by Bill Venners as a community representative. We, at the Scala Center, had the chance to closely collaborate with Eugene Yokota on this proposal.

Motivation

The idea of BSP emerged after facing the fact that the integration of build tools inside IDEs requires a fair amount of work and maintenance effort, which is multiplied by the ever growing number of available build tools.

This integration is often fragile because of the highly customizable nature of build tools. It is quite common for the users of IDEs to experience false compiler errors or out-of-sync state of the dependencies or the generated source files.

By formalizing BSP, we aimed at providing a standard protocol of communication between IDEs and build tools, in which the build tool plays the role of the server that performs the operation requested by the IDE. The ultimate goal being to ease the integration on both sides while providing a better experience to the end-users.

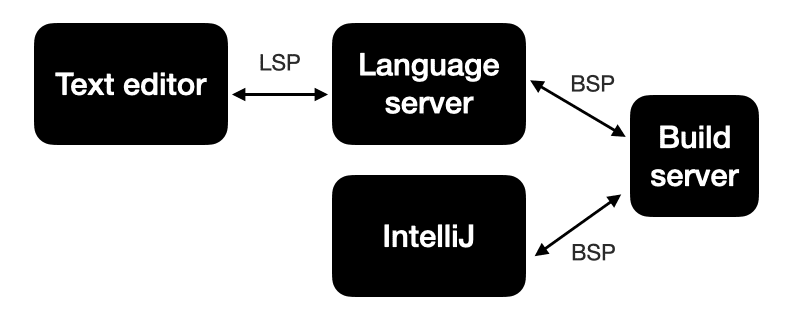

BSP is inspired by LSP, the Language Server Protocol. The main difference being that LSP abstracts over the language whereas BSP abstracts over the build tool.

Metals is both a language server and a build client. It provides text editors with support of the Scala language, enabling code-edition related features such as error reporting, code completion, go-to-definition, and more. But Metals itself depends on a build server to perform build-related operations, such as fetching the dependencies, invoking the compiler, running the tests or the application.

IntelliJ Idea is also a build client, but it does not rely on a language server. It interacts directly with the build server to import the project and perform compilation on save. The Scala language support in IntelliJ is embedded in the Scala plugin.

What’s new

With the recent built-in support of BSP in sbt, it is going to be possible for Metals and IntelliJ to connect to the sbt server and communicate with it directly. This solution is an alternative to the current status quo of using Bloop as a third-party BSP server.

Bloop still offers some advantages compared to sbt server. It can serve several build clients, on different projects, and run the requests concurrently. It also supports DAP, the Debug Adapter Protocol, which provides code editors with the ability to debug applications and evaluate code at runtime.

In contrast, by using sbt as the build server, you avoid potential inconsistencies, you spare duplicated compilation times, and you benefit from the customization of your build inside your IDE.

Choosing Bloop or sbt as the build server depends on the project you are working on and the developer experience you are looking for. In the following paragraph we describe the main characteristics of using sbt as a build server.

The full sbt experience inside your IDE

The Build Server Protocol improves the integration of sbt inside IDEs by leveraging on three sbt core concepts:

- The incremental compiler (aka Zinc): one single compiler for all working environments.

- The build definition: the structure of your build definition mirrors the project structure from your IDE.

- The task graph: the custom tasks and settings of your build are taken into account by your IDE.

The sbt incremental compiler

One good aspect of using sbt as a build server is that you benefit from the sbt incremental compiler in all your working environments: in the sbt shell and the different IDEs you are using.

Let’s take an example that illustrates a traditional workflow of working on an sbt project.

You start by opening your sbt project in IntelliJ Idea, for the purpose of adding a new feature. You reorganize the existing code by moving some classes from module to module. You add a new class, modify a few methods and add a bunch of tests.

During this process IntelliJ Idea compiles the code for you and reports the compilation errors. When you run the tests, it loads the classpath that it has itself compiled and calls the main method of the test framework.

Pleased by the result of your work, you decide to deploy the application. You open the sbt shell and run the package command. sbt does not know that the application has already been compiled by IntelliJ Idea, and so it must recompile the changes you have made since you started working.

If you are like me and you use several IDEs, you might want to try out Metals. You open VS Code and import your sbt project with the Metals plugin. This takes time again because the project is recompiled from scratch by Bloop, which is the build server used by Metals.

All in all, a lot of time is wasted by recompiling the exact same codebase.

With sbt as the build server, the sbt incremental compiler is the one and only compiler for all your working environments:

- You can switch from one IDE to another with no compilation latency.

- You can open two IDEs simultaneously. Each change would trigger a single compiler invocation but both IDEs would be notified of compiler errors.

- At any point in your coding workflow you can run an sbt command and benefit from the fact that the code is already compiled. The tests or the application start without delay.

This kind of workflow was already possible by configuring and using Bloop in all your working environments. The main difference is that it is now natively supported by sbt and it does not rely on a third party.

This feature mixes remarkably well with the new, and experimental, remote caching feature in sbt 1.4.0 (see release note). By enabling remote caching, a new developer can clone an sbt project and start working on it with no initial full compilation.

The sbt build definition

An sbt build definition is made of projects, configurations (Compile, Test, Runtime…) and settings. A project can have an arbitrary number of configurations, which in turn can have an arbitrary number of settings. A BSP workspace, on the other hand, is composed of top-level build targets. A project / configuration scope in sbt becomes a BSP build target if it contains some predefined BSP-related settings. In particular it must contain the bspBuildTargetId setting.

By default those settings are defined on the project / Compile and project / Test scopes, making them two distinct build targets. It means that the main and test sources of your project are compiled separately, each with its own classpath. Of course the project / Test build target depends on the project / Compile one.

You can have additional configurations, such as the IntegrationTest configuration. They will automatically be mapped to more BSP build targets.

It may sometimes be convenient to disable the BSP support on a particular project or configuration. For instance, some projects cannot be compiled incrementally. Or you can have a configuration that is similar to another one in terms of its compiler inputs.

To this purpose you can use the bspEnabled key: the bspEnabled := false setting disables BSP on an entire project, whereas Test / bspEnabled := false setting disables BSP on the Test configuration only.

The BSP structure of an sbt project mirrors the exact structure of the build definition. It is the same across all the environments of the developers working on this project.

The sbt task graph

An sbt build definition is highly customizable. The list of available plugins is very large and covers a lot of use cases.

In addition to plugins, you can shape the task graph of your build by defining new settings and tasks, overloading existing tasks or adding new dependencies between tasks. sbt can merely execute any piece of Scala code at any point in the build task graph.

When sbt receives a BSP request it translates this request into a task execution. This task is no different than any other task. It is a regular sbt task that depends on other well-known sbt tasks and settings.

For instance the buildTarget/compile BSP request is translated into a bspBuildTargetCompile task which depends on the traditional compile task. It means that the BSP buildTarget/compile triggers the execution of the real compile task that is defined in your build definition and so it performs all the custom operations that you have defined.

By using sbt as the build server you bring the level of customization of sbt to the IDE.

The example of source generation

Let’s take a simple example, that is source generation.

sbt gives the ability to automatically generate sources before the compilation happens. This can be done by either adding a custom sourceGenerator or by installing a source generation plugin.

Assume we want to generate some Java code from protobuf files. We can use the sbt-protobuf plugin:

// project/plugins.sbt

addSbtPlugin("com.github.gseitz" % "sbt-protobuf" % "0.6.5")

// build.sbt

lazy val root = project.in(file("."))

.enablePlugins(ProtobufPlugin)

Now we add a src/main/protobuf/SearchRequest.proto file and run the compile command to generate and compile the corresponding java file. sbt goes over the files in src/main/protobuf, runs the protoc command on each file, which generates a java file in the target/scala-2.13/src_managed/java folder. Then it compiles all the generated, as well as the unmanaged sources.

Traditionally, when working in an IDE, we must verify by ourselves that the generated sources are up-to-date. This can be quite cumbersome because each time a .proto file has changed, by a manual edit or a git operation, we must run sbt compile or sbt generateSources manually.

With sbt as the build server, the workflow is greatly simplified because each of the buildTarget/compile requests sent by the IDE will trigger the source generation task. It is worth noting it is efficient because sbt uses a file tracking system to avoid regenerating sources that have not changed.

Other opportunities

The previous example gives us a glimpse at the possibilities opened by BSP in sbt. There are many others, among which we can think of:

- Better support of multi-platform and multi-version projects using

sbt-projectmatrix. - Custom code linting using

sbt-scalafix. - Automated formatting using

sbt-scalafmt.

Wrapping Up

BSP support in sbt is a major milestone in the adoption of BSP in the Scala ecosystem. We hope that it will ease the integration of sbt for the teams working on IDEs and language servers.

We also hope that it will improve the experience of the large group of all sbt users by offering them a unified working environment that meets their needs:

- An optimal workflow for developing, compiling, testing and releasing their project.

- A centralized source of configuration, that is the sbt build definition.

- A high level of customization that is compatible with all environments.

The BSP implementation is very fresh in sbt 1.4.0. No doubt that we will need some time to round the corners. You are nonetheless very much encouraged to give it a try by following the instructions in this Scala contributors post or in the sbt 1.4.0 release note.